I recently did an ignite talk at DevOpsDays Auckland 2019 about GitOps. While doing the deck for the talk, I had a chance to really reflect on question “What is GitOps?”.

I recently did an ignite talk at DevOpsDays Auckland 2019 about GitOps. While doing the deck for the talk, I had a chance to really reflect on question “What is GitOps?”.

Definition

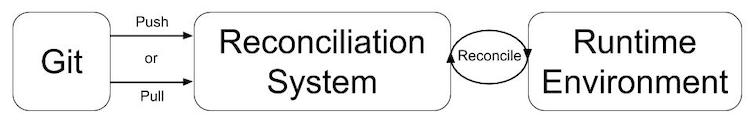

GitOps is reconciling a desired state in Git with a runtime environment.

“But this is what we’ve always done!” you say. You’re right, application code in Git is eventually deployed (reconciled) to a runtime environment. However, operational code and state is another matter. Operational runtime environments are often not based on code, even if they’re in the cloud. Changes are made to those environments by one-time updates via a web interface or command line tool but the desired state is never stored anywhere, only the current state is stored in the runtime environment.

GitOps is the same general Git workflow we’ve known for years with one simple additional step.

- Pull request

- Review

- Merge

- Action

It’s that last step that distinguishes GitOps from the usual Git workflow. Automatically taking action when a commit is merged. That action takes place in a reconciliation system, which is triggered by a push or pull event. That reconciliation system then applies the desired state from Git to a runtime environment.

At a high level it looks like this.

Some examples of the various pieces (the table is meant to be read column-wise).

| Git | Push | Pull | Reconciliation System | Reconcile | Runtime Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GitHub | Webhook | Poll | Flux | SSH | Kubernetes |

| GitLab | Jenkins | File transfer | Cloud (AWS, Azure, GCP, etc.) | ||

| Bitbucket | ArgoCD | API call | A DNS server |

Git is not only the source of truth for your application code but it also becomes the source of truth for your operational code. The reconciliation system could also push commits into Git to reflect a new state due to automatic events in the runtime environment (e.g. auto scaling to 5 VMs).

There have been a number of definitions of GitOps offered. Most notably from WeaveWorks, the people who coined the term GitOps. However, I found that their definition and others are very Kubernetes centric and doesn’t capture the essential elements of a what is actually a more general technique.

Use Cases

Here are a handful of use cases where you could apply GitOps. Of course, it’s not limited to these and I’d be interested to hear if you’ve applied GitOps to any other use cases.

Deployment

Deployment is one of the most common use cases for GitOps. You need to deploy a new version of some software to an environment so you make a change in Git and that software is automatically deployed to your runtime environment. Flux is a Kubernetes operator for doing so. I also built a system for doing so that I wrote about in GitOps Driven Deployments on OpenShift.

Infrastructure

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) (e.g. Terraform, CloudFormation, etc.) is perhaps the canonical use case for GitOps. You need to change your infrastructure in some way (e.g. add a VM) so you update your IaC in Git and that change is automatically run on your infrastructure. This can be done by your reconciliation system executing commands that apply the configuration to the infrastructure.

DNS

I found the paper GitOps: A Path to More Self-service IT by Thomas A. Limoncelli really inspirational. The author does an excellent job of describing GitOps in much more general terms. The primary use case he offers as an example is for DNS.

In the author’s own words,

Initially the DNSControl configuration file (dnsconfig.js) is stored in Git. A CI system is configured so that changes trigger the test-and-push cycle of DNSControl, and updates to the file result in the changes propagating to the DNS providers. This is a typical IaC pattern. When changes are needed, someone from the IT team updates the file and commits it to Git.

This is exactly how I’ve been thinking about GitOps.

On/Off Boarding People

People come and go from teams all the time. When they arrive, you have to add them to Slack, GitHub, JIRA, and all of the other systems you use to get work done. Imagine a file full of user information like this.

users:

- name: Jack Burton

active: true

email: jack.burton@porkchopexpress.com

slack: jack-burton-me

github: jburton

- name: Gracie Law

active: true

email: gracie.law@porkchopexpress.com

slack: girl-with-the-green-eyes

github: glaw

- name: David Lo Pan

active: false

email: david.lo.pan@wingkongexchange.cn

slack: lo-pan

github: dlpan

When a user is added/removed to/from the list, they are added/removed to/from those systems by your reconciliation system.

Tooling

A lot of tooling already has Git integration so customising tools to do GitOps isn’t much of a stretch in many cases.

There is also tooling cropping up that supports the GitOps technique directly:

Barriers

Naturally there are barriers to the adoption of any new technique.

ITIL

If you’re in a traditional ITIL shop, they likely have very particular processes you need to follow to implement a change. For GitOps to gain adoption, you may need to take the ITIL stalwarts along on the journey and show them how GitOps actually implements ITIL practices. And if there are parts of the process you can automate, such as opening/closing tickets, look for opportunities for your reconciliation system to integrate with ITSM systems (e.g. ServiceNow) in order to do so. I’d love to see these sorts of processes coalesce around the pull request and do away with any unnecessary ceremony.

Git as SPOF

If GitOps is driving your runtime environments, Git uptime is even more critical. Git can become a single point of failure (SPOF) for essential business processes. If you use a cloud based Git service and they have a bad day, you’re going to have a bad day. If you run Git on-premise, you’ll almost certainly want to configure it to be highly available. Either way, you’ll need to seriously consider the impact on your business of Git being down.

Secrets Management

Proper secrets management in any system is a tough nut to crack. Your reconciliation system needs to have access to a lot of credentials so it can update runtime environments. There are a lot of secrets management systems (e.g. Vault, CyberArk, etc.) that you can use to safely store the secrets that the reconciliation system needs to get its work done. And, of course, you want to follow best practices like only using service accounts that have exactly the permissions they need.

Proper secrets management in any system is a tough nut to crack. Your reconciliation system needs to have access to a lot of credentials so it can update runtime environments. There are a lot of secrets management systems (e.g. Vault, CyberArk, etc.) that you can use to safely store the secrets that the reconciliation system needs to get its work done. And, of course, you want to follow best practices like only using service accounts that have exactly the permissions they need.

Benefits

In my experience I’ve found a number of benefits of GitOps.

Git System Features

There are many features of any modern Git system that we take for granted that are beneficial for GitOps. The role based access control (RBAC) can be used to grant access to those who can propose change and those who merge change (which implies automatic action). Being able to edit a file and propose a pull request directly from the web interface is amazingly powerful for those unfamiliar with Git. Even just getting email or Slack notifications when a pull request is proposed is helpful.

Versioning

Versioning absolutely everything that goes into your runtime environment provides many benefits. Perhaps you reconcile on every commit. In that case you may want to record the short SHA of the commit as the version of the runtime environment. Or perhaps you reconcile when a tag is pushed. In that case you may want to record the tag as the version of the runtime environment. Whatever you do, you want to know exactly what code is in your runtime environment and any point in time.

Audit

Even compliance and audit benefit from GitOps. Being able to use Git history to show how and why a runtime environment is in the state it’s in is helpful for compliance. Being able to use Git history to show who proposed a change, who reviewed and approved it, and who merged it is essential for audit. In one instance, an auditor interviewed me and we got through the session in half the time because I was able to show him how we were driving deployments with GitOps with all of the benefits above.

Self-service

The biggest benefit is self-service. Those that need to make the change are those that propose the change. Even if they’re not familiar with Git, they’re able to use the web interface to propose the changes they need. The whole system is transparent and you’re able to understand the state it’s in, even if you don’t have direct access to the runtime environment.

The biggest benefit is self-service. Those that need to make the change are those that propose the change. Even if they’re not familiar with Git, they’re able to use the web interface to propose the changes they need. The whole system is transparent and you’re able to understand the state it’s in, even if you don’t have direct access to the runtime environment.

Coda

GitOps is a general technique that is applicable to many use cases. It’s far more than just Kubernetes. The barriers to adoption are relatively low and I think it has the potential to be a widely adopted way of working once people start to understand the benefits they can realise from it. Frankly, I just want to see more GitOps in the world.